Rimfire vs. Centerfire Ammo: A Comparison

Written By

Michael Crites

Licensed Concealed Carry Holder

Reviewed by

Editorial Team

Learn About The Editorial Team

Share:

Products are selected by our editors. We may earn a commission on purchases from a link. How we select gear.

Updated

Jun 2025

For some people in the shooting community, choosing ammunition can be a little daunting. There are a lot of bullets out there – which makes for a steep learning curve, especially when it comes to teasing out the relative strengths of different calibers and ammunition types.

At first glance, all ammunition might look pretty similar – a metal case with a bullet on one end and some kind of firing mechanism on the other. But here’s the thing: the design differences between rimfire and centerfire cartridges can make a huge difference in performance, cost, reliability, and what you can actually do with them. These distinctions affect everything from how much you’ll spend on a range day to which rifle you’ll want for your next hunting trip.

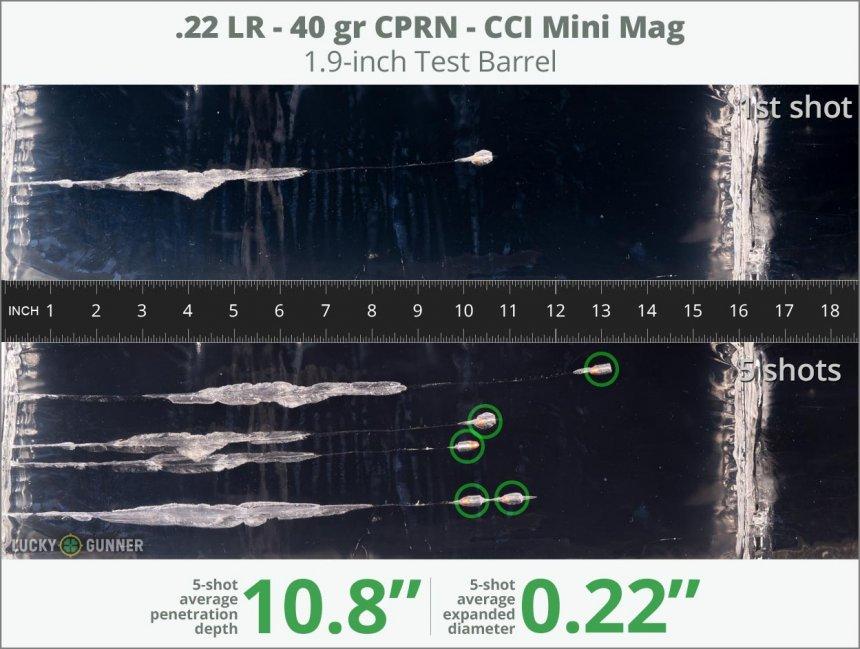

Rimfire ammunition – think your classic .22 LR – is affordable and gentle, making it perfect for new shooters and anyone who wants to burn through 500 rounds without breaking the bank. Centerfire ammunition, from 9mm pistol rounds to powerful rifle cartridges, brings the reliability and stopping power you need for serious work.

We’re going to take a deep dive into both types, comparing how they work, what they cost, and when you’d want to use each one.

This article is part of our series on Gun Basics.

In This Article

Ammunition Fundamentals

Before we dive into the nitty-gritty differences between rimfire and centerfire, let’s cover the basics. Modern ammunition is actually pretty elegant in its simplicity – everything you need to send a bullet downrange is packaged into one neat little unit.

The Four Essential Components

Every cartridge has four main parts working together: the case, bullet, powder, and primer. The case – usually made of brass, though you’ll also see steel, aluminum, and nickel – holds everything together and provides the structure. On one end sits the bullet that’s going to fly toward your target. Inside the case is the powder charge that creates the pressure to push that bullet out. And somewhere on the case is the primer, which is basically the match that lights the whole thing off.

How It All Works

The firing sequence is the same whether you’re shooting a tiny .22 or a massive .50 caliber round: when you pull the trigger, a firing pin or hammer strikes the primer, which ignites and creates a small explosion.

That explosion lights off the powder charge, which burns rapidly and creates a lot of gas pressure. This pressure forces the case to expand against the chamber walls (sealing everything up tight) while simultaneously pushing the bullet down the barrel and out toward whatever you’re aiming at.

Self-contained metal cartridges are substantially more wear- and weather-resistant than the individual components. Not to mention faster to reload and considerably more convenient to pack around.

In addition to the additional convenience and durability the cartridge-based round also introduced much more consistency in manufacture, increasing reliability and unlocking innovation that has allowed almost every different caliber of round to become better over time.

All bullets are fired the same way – a striker or a hammer hits and ignites the primer, which detonates the powder and sets off a small explosion, forcing the cartridge to expand, sealing the chamber, and sending the bullet on its merry way. Both rimfire and centerfire cartridges work this way. There are some big differences, however, when it comes to the primers.

What is rimfire ammunition?

Generally, rimfire cartridges work exactly as described above. What makes them special is — as you might infer by the name — the primer extends all the way to the rim of the cartridge. The firing pin strikes that rim to fire the round. Like any type of technology, this has some pros and cons.

In terms of pros, the manufacturing process requires less precision, making rimfire ammunition more affordable than precision cartridges with tighter tolerances. That’s one of the reasons almost every firearm enthusiast has at least one .22LR gun: you can afford to shoot them all day.

They also tend to be used in small caliber firearms with lower pressure rounds because the wall of the cartridge has to be thin enough to be crushed by the firing pin. This makes rimfire firearms great for training new shooters thanks to their miniscule recoil.

As for the cons, the biggest two are reliability and magazine loading. Because rimfire ammo is manufactured with — uh — generous tolerances it can also be inconsistent.

That said, quality ammo is still affordable and will almost certainly work well for most firearms.

Rimfires also have a larger base rim than their centerfire counterparts: which prevents them from stacking well in a vertical orientation. This can create feeding issues in magazines, so you’ll generally see .22LR rifles with rotary magazines, which are slow to reload and limit capacity to about 10 rounds.

When it comes to price-per-round the .22LR reigns supreme as it’s easily the most affordable cartridge available. This factor alone will keep this little rimfire champ in circulation for the foreseeable future.

Rimfire Ammo Examples

.22LR

This is, for most folks, the first round they ever fire. It’s cheap, easy to find, has virtually no recoil, and is perfect for learning how to shoot.

The .22LR has come a long way since hitting the market in 1884 – offering more reliability and variation over the years, with it now being the go-to round for varmint hunting. It’s awfully hard to top the fun of spending an afternoon plinking through 500 rounds with a Browning SA22 for just a few bucks.

.17 HMR.

A newer entry into the rimfire universe, the .17 HMR – or Hornady Magnum Rimfire – was developed in 2002 by necking down a .22 Magnum case to the smaller .17 caliber. The 17 grain projectile rips along with a muzzle velocity of around 2,600 ft/sec, or about 50 faster than a typical .22LR round.

This makes it an outstanding varmint hunting and target shooting round out to a few hundred yards.

What is Centerfire Ammunition?

Centerfire rounds work on the same general principle as rimfire, except the primer is independent from the case and press-fit into the rear of the round. This primer is struck by the firing pin, setting off the chain reaction resulting in a round being fired. Centerfire rounds have a tighter rim-to-casing ratio, enabling them to stack more efficiently in magazines than rimfire rounds.

Additionally, this design means that much higher pressures can be achieved, which is why basically all larger caliber rounds are centerfire. They can also be reloaded with relative ease, making them a popular choice with reloading enthusiasts & thrifty shooters.

Centerfire rounds have more components, which means they cost more to make and, in-turn, shoot.

Centerfire Ammo Examples

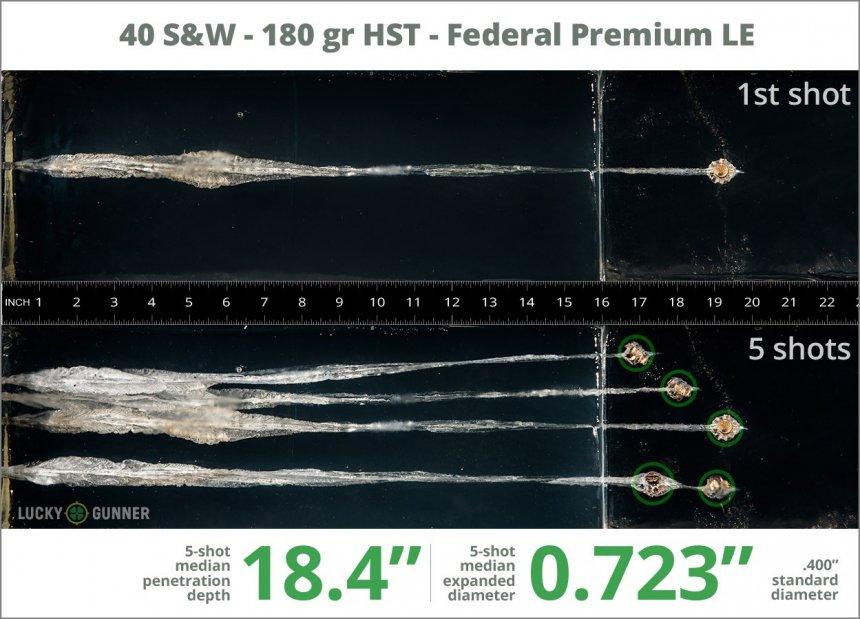

.40 Smith & Wesson

The .40 S&W. is the 40 cal big brother to 9mm, meant to bridge the gap between the size of the 9mm and the classic .45ACP. This round is an excellent, if now a little niche, defensive handgun round that packs considerable stopping power. Any semi-automatic handgun in .40 S&W or 9mm is an excellent carry choice.

There’s some debate between the two and while the .40 S&W has more energy and superior ballistics, the 9mm is a more than capable round in its own right thanks to additional carry capacities and lower recoil.

5.56mm NATO

The 5.56mm demonstrates the difference between rimfire and centerfire cartridges well. Despite a bullet with roughly the same diameter as a .22LR rimfire, this round packs a lot more pressure behind the bullet, and thus is effective at combat out to 500 yards or so in skilled hands.

Other fantastic examples of centerfire rifle ammunition include the big brother to the 5.56, the 7.62×39, the classic .308, and AR-15 pistol-friendly .300 BLK.

Comparing The Two

Now that we’ve covered the basics, let’s get down to the real differences between rimfire and centerfire ammunition. While both types follow the same general firing principle, their design differences create some pretty significant variations in performance and application.

Key Differences

Primer Location Here’s where things get interesting. Rimfire cartridges have their priming compound spread around the entire rim of the case – hence the name. It’s literally built into the rim itself. Centerfire rounds, on the other hand, have a separate primer that’s press-fit into a pocket at the center of the case head. This might seem like a small detail, but it affects pretty much everything else about how these cartridges perform.

Ignition The firing sequence looks different too. With rimfire ammo, the firing pin has to strike and actually crush part of that rim to ignite the priming compound – which is why rimfire cases have to be made with thinner walls. Centerfire ammunition gets hit right in the center, where that separate primer sits waiting to do its job. It’s a more direct, concentrated impact.

Reliability This is where centerfire really shines. Because the priming compound is concentrated in one spot rather than spread around a rim, centerfire rounds tend to be more consistent and reliable. That thin rim on rimfire cartridges can sometimes fail to ignite properly, especially with cheaper ammunition. Quality rimfire ammo has gotten much better over the years, but centerfire still wins the reliability contest.

Power Centerfire ammunition can handle significantly higher pressures, which translates to more power. Those thicker case walls can contain much more substantial powder charges without blowing apart. This is why you won’t find any rimfire cartridges in serious hunting or defensive calibers – they just can’t generate the pressure needed for that level of performance.

Reloadability Here’s a big practical difference: centerfire cases can be reloaded multiple times, while rimfire cases are generally one-and-done. Since the rimfire’s rim gets crushed during firing, there’s no practical way to restore it for reuse. Centerfire primers can be punched out and replaced, making reloading not just possible but popular among enthusiasts who want to save money or customize their loads.

| Feature | Rimfire | Centerfire |

|---|---|---|

Primer Location | Spread throughout the rim | Separate primer in center pocket |

Ignition Method | Firing pin crushes rim | Firing pin strikes center primer |

Case Wall Thickness | Thin (must be crushable) | Thick (handles high pressure) |

Reliability | Good (quality dependent) | Excellent (more consistent) |

Power/Pressure | Low to moderate | Low to very high |

Reloadability | No (rim gets damaged) | Yes (multiple reloads possible) |

Cost per Round | Very low | Low to high |

Typical Applications | Training plinking small game | Everything from target to big game |

Common Examples | .22 LR .17 HMR .22 WMR | 9mm .308 .45 ACP 5.56mm |

Which is better?

Regardless of if you’re shooting rimfire or centerfire ammo, there are lots of great options out there. And what you choose should ultimately be informed by your use case and what you hope to achieve with it.

Additional Resources

- Roy Chesson, Rimfire vs Centerfire: Which is Better for You?, April 22, 2019

- Wikipedia article, Rimfire ammunition

- Wikipedia article, Centerfire ammunition

- Wikipedia article, .17 HMR

- M Carbo, 17 HMR vs 22LR

- gundata.org, 17 HMR Ballistics Chart & Drop Table

- detecting.us, Civil War Bullet Reference Guide

- LuckyGunner, .22LR Ballistics Gel Test

Updated

June 1, 2025 — Restructured article with improved organization and added comprehensive comparison section including quick reference table highlighting key differences between rimfire and centerfire ammunition.

Sign up for our newsletter

Get discounts from top brands and our latest reviews!