Bullet Sizes: Understanding Sizes, Types, and Calibers

From the humble .22 LR to the classic .45 ACP, explore the vast range of bullet sizes & types. We dive into history & the development of today's most popular types of ammo.

Written By

Kenzie Fitzpatrick

Competitive Shooter

Edited By

Michael Crites

Licensed Concealed Carry Holder

Share:

Products are selected by our editors. We may earn a commission on purchases from a link. How we select gear.

Updated

Jun 2025

Modern small arms ammunition can be confusing due to the myriad common types, calibers, and sizes involved, but with a little research, navigating the “bullet aisle” at your local gun store is a snap. We’re here to hold class on the essentials. This article is part of our series on Gun Basics.

If you’re in the market for ammo check out our guide to the best places to buy ammo online.

In This Article

What is ammunition, anyway?

At its most basic level, ammunition is a single, complete package designed to propel a projectile from a firearm using controlled explosive force. Whether you’re shooting a .22 rifle at tin cans or a 12-gauge shotgun at clay pigeons, the fundamental principle remains the same: a controlled explosion pushes a projectile down the barrel and toward your target.

The Four Essential Components

Modern ammunition consists of four critical components working together as a complete system:

The Case (or Hull) serves as the foundation that holds everything together. Made from materials like brass, steel, aluminum, or plastic (for shotgun shells), the case contains the other components and provides the structural integrity needed to withstand the explosive forces during firing. The case also seals the chamber, preventing hot gases from escaping backward toward the shooter.

The Primer acts as the ignition system. When struck by the firing pin, this small, impact-sensitive explosive charge creates the spark needed to ignite the main powder charge. Think of it as the match that lights the fire.

The Powder (also called propellant) is the controlled explosive that generates the gas pressure needed to propel the bullet. Modern ammunition uses smokeless powder, which burns rapidly and consistently to create expanding gases that push the projectile down the barrel.

The Projectile is what actually travels to the target. In rifle and handgun ammunition, this is typically called a bullet. In shotgun ammunition, it might be multiple pellets (shot) or a single large projectile (slug). The projectile carries the energy to the target and determines much of the ammunition’s performance characteristics.

How It All Works Together

When you pull the trigger, a precisely orchestrated sequence occurs in milliseconds. The firing pin strikes the primer, which explodes and ignites the powder charge. The burning powder rapidly expands into hot gases, creating tremendous pressure inside the sealed case. This pressure has only one place to go: it pushes the projectile out of the case and down the barrel at high velocity.

The case remains in the chamber (in bolt-action rifles) or is ejected from the firearm (in semi-automatic weapons), while the projectile continues toward the target carrying the energy generated by the controlled explosion.

Why This Matters for Shooters

Understanding ammunition as a complete system helps explain why you can’t simply mix and match components from different cartridges. Each ammunition type is engineered as a balanced system where the case size, powder charge, primer strength, and projectile weight work together to produce safe, consistent performance.

This is why a .308 Winchester cartridge won’t work in a .30-06 rifle even though both use similar bullets – the cases are different lengths and the powder charges are designed for different chamber pressures. Similarly, this system approach explains why handloading (reloading your own ammunition) requires careful attention to established load data rather than guesswork.

Why This Matters for Shooters

Understanding ammunition as a complete system helps explain why you can’t simply mix and match components from different cartridges. Each ammunition type is engineered as a balanced system where the case size, powder charge, primer strength, and projectile weight work together to produce safe, consistent performance.

This is why a .308 Winchester cartridge won’t work in a .30-06 rifle even though both use similar bullets – the cases are different lengths and the powder charges are designed for different chamber pressures. Similarly, this system approach explains why handloading (reloading your own ammunition) requires careful attention to established load data rather than guesswork.

Cartridge vs. Bullet: Getting the Terms Right

One of the most common misconceptions is calling the entire package a “bullet.” Technically, the bullet is just the projectile – the part that leaves the barrel. The complete package including case, primer, powder, and bullet is properly called a cartridge (for rifles and handguns) or a shell (for shotguns).

Using correct terminology isn’t just about being precise – it helps when communicating with other shooters, reading technical information, or purchasing ammunition. When someone says they need “9mm bullets,” they probably mean complete 9mm cartridges, but the distinction matters when discussing reloading or technical specifications.

The Modern Advantage

Today’s factory ammunition represents over 150 years of engineering refinement. Modern cartridges are manufactured to incredibly tight tolerances, ensuring consistent performance, safety, and reliability that early shooters could never have imagined. Quality control systems monitor everything from powder charges measured to fractions of a grain to bullet seating depth precise to thousandths of an inch.

This consistency means that when you buy a box of ammunition from a reputable manufacturer, each cartridge should perform nearly identically to every other cartridge in that box – and to other boxes of the same specification. This reliability forms the foundation that allows modern firearms to achieve remarkable accuracy and dependability.

The History of Bullets

Early firearms used lead balls as projectiles before the development of modern bullets.

Ready-to-fire cartridge-based ammunition has been around for just over 200 years, with Swiss gunsmith Jean Samuel Pauly usually credited with making the first integrated “needle-fired” round in 1808. Fast forward to 1846, and Parisian gunsmith Benjamin Houllier had begun to patent more successful rimfire and centerfire cartridges.

By the time of the Civil War, both breechloading longarms, such as the Spencer and Sharps Carbines and Henry lever-action rifles, along with revolvers such as the Smith & Wesson No. 1 were in circulation throughout the United States, all using cartridges instead of cap-and-ball black powder muzzle-loaded rounds.

Within a short generation of that conflict, most modern firearms were cartridge-based, with muzzleloaders considered today to be primitive.

Bullet Calibers, Millimeters, or Gauge?

One thing that is abundantly clear to all gun owners is that you should only try to load ammunition into a firearm that it is designed for.

Modern firearms make it (relatively) easy

All modern firearms will list the bullet chamber size either on the frame/receiver or the barrel. On pistols, revolvers, and rifles made in the U.S. or Great Britain, that size will typically be listed in terms of 1/100th (hundredth of an inch), a portion deemed a “caliber.”

For instance, a firearm with a quarter-inch bore will be “.25-caliber.” For pistols, revolvers, and rifles made in areas that have long been on the metric system, the bore will be in millimeters.

This rule largely converts back and forth with such general examples as 5.56mm/.223-caliber, 6.35mm/.25-caliber, 7.62mm/.30-caliber, 11.43mm/.45-caliber, and so forth.

Metric cartridges will include the case length

Added to this in metric cartridges is typically the length of the cartridge’s case. For instance, an 11.43x23mm round has an 11.43mm (.45-caliber) bullet diameter on a case that is 23mm long. Cartridge length is a key dimension for ensuring proper fit and function in firearms.

On this side of the pond, rather than specify the bullet diameter and the length of the case, we typically just label a cartridge by caliber and who invented it. However, understanding the dimensions of a cartridge, including case length and bullet diameter, is essential for compatibility.

For example, instead of 11.43x23mm, Americans would call the same round a .45ACP, with the abbreviation standing for Automatic Colt Pistol. Clear as mud?

Shotguns go it alone

When it comes to shotguns, all the above logic goes out the window and is substituted in English-speaking countries with the terms “gauge” or “bore,” with both being a throwback to the days of old smoothbore muskets and fowling pieces and the size determined by a theoretical weight in pounds of the largest lead ball that could roll down its barrel, with higher numbers meaning a smaller gauge and lower numbers a larger gauge.

For example, a 12-gauge shotgun, which has a 73-caliber barrel, could accommodate a lead ball that weighed 1/12th of a pound. A 20-gauge shotgun, which has a comparatively smaller 62-caliber barrel, could only accommodate a 1/20th pound ball.

Larger gauges, such as 10-gauge, are associated with increased power and heavier recoil due to their larger bore size and are often used for more demanding applications.

Of course, all shotguns today use plastic-hulled shells rather than one big honking lead ball, but the peculiar unit of measure holds.

Cartridge Components Deep Dive

Headstamps

One great thing about modern ammunition is that the head of the case (or bottom of the bullet, depending on which end is up) typically carries the story of what kind of load it is.

Usually, headstamps will include the caliber, manufacturer, and sometimes other relevant information such as when it was produced or if it is a special load such as with a heavy powder charge, denoted as “+P.” Some headstamps may also indicate rim diameter, which is important for ensuring ammunition compatibility with different firearms.

To be safe, learn to understand what the headstamps mean on your ammunition and compare it to the chambering markings on the barrel or receiver of your firearm before loading.

Cases and Case Materials

A cartridge case is the component that holds the bullet, powder, and primer together. Early 1800s-era cartridges had cases that were made of a variety of materials that matched their period. This included paper, bronze, drawn brass, and “Japanned” tin.

Today, only modern “yellow” brass remains in factory-produced cartridges while other materials such as nickel, aluminum, and steel are regularly encountered.

Brass vs. Steel vs. Nickel Cases

Brass is the most common as it yields a case that can usually be reloaded several times but can easily tarnish. Aluminum-cased cartridges are typically just seen used for target shooting loads but due to their nature when compared to copper-based brass cases, are cheaper.

Steel-cased ammunition, typically from Eastern Europe, is likewise economical but sometimes has a bad reputation of “sticking” in modern autoloaders, especially if shot in quantity.

Meanwhile, Nickel plated brass-cased ammo is used in many premium hunting and defense loads and is more corrosion-resistant, a bonus for cartridges that may be exposed to harsh elements.

On the other hand, hulls on shotgun shells have been plastic for generations, upgraded from all-brass or paper hulled shells.

Bullet Types and Construction

Different bullet designs influence terminal ballistics, which refers to how the bullet behaves upon impact with a target, affecting penetration, expansion, and energy transfer.

The science of ballistics covers the study of bullet behavior both in flight (external ballistics) and upon impact (terminal ballistics), helping to evaluate ammunition effectiveness and firearm performance.

When cartridges first hit the market in the 19th Century, the common bullet used was a variation of a simple lead round-nosed projectile.

This standard was maintained into the early 20th century and can still be found today– abbreviated on ammo boxes as “LRN” — and is a good choice for cheap target rounds.

Moving beyond the simple LRN

The type of bullet has diversified from that basic LRN over time. The goal being to provide better performance for a range of purposes, and includes a copper jacket over the lead bullet to cut back on fouling and yield a better aerodynamic projectile, imparting more accuracy at distance and better penetration, as the old LRN lead head deforms and lumps when it meets resistance.

Additionally, rifling—spiral grooves cut into the barrel—imparts spin to the bullet, which improves stability and accuracy.

Such jacketed bullets are typically referred to as having a full metal jacket, or “FMJ.”

Mmmm… expansion…

To help increase expansion (which dumps more of a bullet’s energy into the target, increasing stopping power and making them ideal defensive or concealed carry rounds) the nose of a bullet is left unjacketed and hollowed out, making the lead core mushroom.

Such rounds are typically referred to as jacketed hollow-points, or “JHP,” cartridges. Naturally, there are many other variations, but the above three or combinations of them cover most loads.

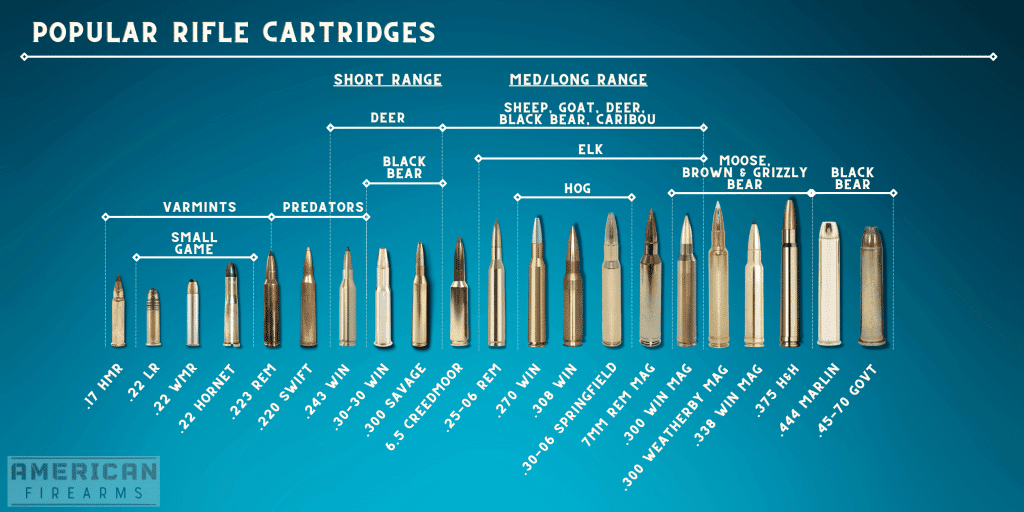

Rifle Cartridges

The below bullet caliber chart gives you a sense of the sizes and applications for various rifle caliber bullets. The chart highlights common calibers that are commonly used for different shooting applications.

While it’s not a complete ammo size chart — there are far too many rounds in the wild to fit them into an easy-to-read bullet size chart — we’ve done our best to cover the most popular rifle calibers.

Small Caliber High-Velocity Rounds

5.56 NATO/.223 Remington

“America’s Rifle,” the AR-15, of which more than 18 million are in circulation, is typically chambered in this common caliber.

Thanks in part to the ubiquitousness of the AR, the 223 Remington is one of the most popular centerfire rifle cartridges anywhere. The 5.56x45mm variation is its military version, and it is the standard issue service rifle cartridge for NATO forces (as well as many non-NATO countries) around the world.

The 223 Remington originated in the 1950s as the 222 Remington. When the US military wanted a new high-speed, small-caliber 308 Winchester replacement, Remington lengthened the 222 case and increased gun powder capacity by about 20%, leading to the creation of the 222 Remington Magnum in 1958.

While the cartridge wasn’t a hit with the military brass it was introduced commercially and lead to another stretched 222 — the 5.56x45mm in 1964. This cartridge was adopted by the military in their new M-16 rifle, setting the stage for 5.56x45mm centerfire domination.

Ranging in size from 55- to 77-grain loads, it is hyper-accurate and great for both short and long-range shooting – even in budget rifles. The 223 Remington is also commonly chosen for varmint hunting due to its flat trajectory and effectiveness against small pests.

While the 223 Rem and 5.56x45mm are very similar, they are not the same cartridge. For those interested, we break down the differences between these two near twins.

.22-250 Remington

The .22-250 Remington stands as one of the fastest commercially available .22-caliber cartridges, pushing lightweight bullets at velocities exceeding 4,000 feet per second.

Originally developed as a wildcat cartridge in the 1930s and commercialized by Remington in 1965, this round excels at long-range varmint hunting and prairie dog shooting.

Its exceptional flat trajectory and explosive terminal performance make it devastating on small game and predators out to 400+ yards. The high velocity does create significant barrel wear and the lightweight bullets can be affected by wind, but for dedicated varmint hunters seeking maximum reach and dramatic terminal effects, the .22-250 remains a top choice among precision shooters.

.243 Winchester

Introduced in 1955, the .243 Winchester represents the perfect balance between manageable recoil and effective performance, making it ideal for young or recoil-sensitive shooters. This versatile cartridge handles everything from varmints with lightweight 55-grain bullets to deer-sized game using heavier 100-grain projectiles.

Based on the necked-down .308 Winchester case, the .243 delivers flat trajectory and excellent accuracy while producing mild recoil that won’t intimidate new shooters. Its dual-purpose nature – equally at home on groundhogs at 300 yards or whitetail deer at reasonable hunting distances – has made it a staple in American gun cabinets.

Factory ammunition is widely available in various bullet weights and styles for different applications.

Intermediate Cartridges

7.62x39mm

Developed as an intermediate cartridge in World War II, as Moscow’s answer to the German 7.92x33mm Sturmgewehr-series rifles, which the Russians were increasingly recovering on the battlefields of the Eastern Front, the 7.62x39mm was first fielded in the SKS rifle.

However, it went on to become best-known for its use in Mikhail Kalashnikov’s AK-47/AKM/RPD and RPK platforms.

A brute of a round, typically seen in about 122-grain loads, it is respected around the globe. The 7.62x39mm is capable of delivering effective stopping power out to moderate ranges, making it suitable for hunting medium-sized game and for self-defense.

We cover the best 7.62×39 rifles if you’re looking to set yourself up with some stopping power.

.300 Blackout

The .300 AAC Blackout (also known as .300 BLK) represents one of the most successful new cartridge introductions of the 21st century, designed specifically to maximize the potential of short-barreled rifles and suppressed firearms. Developed by Advanced Armament Corporation in collaboration with Remington around 2010, this cartridge was engineered to provide .30-caliber performance in the AR-15 platform.

The .300 Blackout’s brilliance lies in its dual personality. With lightweight bullets (110-125 grains), it achieves velocities similar to the 7.62x39mm, providing excellent terminal performance on medium game and two-legged threats. When loaded with heavy subsonic bullets (190-220 grains), it operates quietly when suppressed while maintaining lethal effectiveness at close to moderate ranges.

Based on the .223 Remington case shortened and necked up to .30 caliber, the .300 Blackout requires only a barrel change in most AR-15s – the bolt, magazines, and other components remain identical to standard 5.56 NATO setups. This compatibility has driven widespread adoption among both civilian shooters and military special operations units.

The cartridge excels in short-barreled rifles where the .223 Remington loses significant velocity. Even from 8-10 inch barrels, the .300 Blackout maintains effective terminal performance out to 200-300 yards with supersonic loads, while subsonic ammunition provides Hollywood-quiet suppressed shooting for close-range applications.

Ammunition availability has grown dramatically since introduction, with most major manufacturers offering various loads. While more expensive than .223 Remington, the .300 Blackout fills a unique niche for suppressed shooting, home defense with short rifles, and hunting in areas where rifle restrictions favor shorter barrels. Its versatility and AR-15 compatibility ensure continued popularity among modern sporting rifle enthusiasts.

6.5mm Grendel

Developed by Bill Alexander and Arne Brennan in the early 2000s, the 6.5mm Grendel was designed to overcome the long-range limitations of the 5.56 NATO while maintaining compatibility with the AR-15 platform. This innovative cartridge uses a modified 7.62x39mm case necked down to accept high-ballistic-coefficient 6.5mm bullets, creating a round that significantly outperforms the .223 Remington at extended distances.

The Grendel’s key advantage lies in its ability to maintain supersonic velocity and energy well beyond 800 yards – distances where the 5.56 NATO begins to lose effectiveness. Using bullets ranging from 90 to 130 grains, the cartridge delivers exceptional accuracy and consistent terminal performance on medium game. The higher sectional density and ballistic coefficient of 6.5mm projectiles provide superior wind resistance and retained energy compared to lighter, faster bullets.

For AR-15 owners seeking enhanced long-range capability without switching to a larger, heavier platform like the AR-10, the 6.5mm Grendel offers an ideal solution. The cartridge requires only a barrel and bolt change in most AR-15 rifles, making it a popular choice for precision rifle competitions and hunting applications where longer shots are common.

Magazine capacity is reduced compared to .223 Remington (typically 25 rounds versus 30), and ammunition costs more than standard 5.56 NATO, but the performance gains make these trade-offs worthwhile for many shooters. The Grendel has gained significant traction in competitive shooting circles and among hunters who appreciate its ability to cleanly take deer-sized game at extended ranges.

Full-Power Cartridges

Many of these calibers are suitable for hunting large game and produce more recoil than smaller calibers.

7.62 NATO/.308 Winchester

Developed in the 1950s from the Prohibition-era .300 Savage, to replace the long-serving .30-06 in U.S. military service, the 7.62x51mm cartridge went on to be adopted by NATO and just about every classic battle rifle such as the FN FAL, Beretta BM-59, and M-14, which were all chambered for it.

An incredibly popular hunting round, you’ll likely find a .308 Win on any hunt.

Offering up to a 180-grain pill, it is big medicine in a small package.

.30-06 Springfield

Developed to upgrade the short-lived Springfield .30-caliber M1903 cartridge, which was adopted with the bolt-action Mauser-style rifle of the same name, the slightly shorter 7.62x63mm Springfield .30-caliber M1906 cartridge– abbreviated to .30-06, or just “Aught Six” in gun circles, remained the U.S. military standard through 1957.

As millions of American men carried weapons chambered in the powerful caliber across two world wars and the Korean conflict and trusted it, the round used by Sergeant York and Audie Murphy endures in not only vintage American milsurp rifles but also millions of bolt guns sold to deer hunters over the past century.

Most military rifle bullet rounds hover around 150-grains while sporting offerings run up to 200. The .30-06 Springfield is especially known for its ability to kill large game at considerable distances, making it a popular choice among hunters.w

.270 Winchester

Also developed from the .30-03 Government, although using a smaller .270-caliber bullet, the .270 Winchester has been on the market since the 1920s and is a go-to with American sportsmen for anything whitetail-sized and up.

Today, if a North American gunmaker has a bolt-action deer rifle in their catalog, you can guarantee that .270 Win is one of the options it offers.

Typical loads run about 130-grains.

6.5mm Creedmoor

A relatively new cartridge, the 6.5x48mm Hornady Creedmoor, which only dates back to 2007, has become widely popular, as evident from the available rifles chambered for this round.

Similar in size to the famed Swedish Mauser round, loved by hunters on several continents, the flat-shooting 6.5CM delivers better performance than that vintage cartridge due to having a superb ballistic coefficient, allowing it to stretch out to beyond 1,000 yards even in short-action bolt guns and AR-10s chambered for it.

Its high muzzle velocity also contributes to a flatter trajectory and improved long-range accuracy.

Before the introduction of the Creedmoor, such distances were considered off-limits except for the best marksmen.

Typical loads run in the 130-grain range.

The 6.5mm Creedmoor represents the most successful new cartridge introduction in decades, transforming from a specialized precision shooting round to mainstream hunting and target cartridge in just over 15 years.

The Creedmoor was designed to maximize the ballistic potential of 6.5mm bullets within the constraints of short-action rifles and standard magazine lengths. Built on a modified .30 Thompson Center case, the 6.5mm Creedmoor achieves its exceptional performance through careful engineering rather than raw power.

The cartridge’s moderate case capacity and 30-degree shoulder angle create consistent powder burn and optimal pressure curves, while the short overall length allows use of high-ballistic-coefficient bullets without seating them deeply into the case. What makes the Creedmoor special is its ability to deliver match-grade accuracy with manageable recoil. Factory loads typically push 140-grain bullets at 2,700 feet per second, generating significantly less felt recoil than larger cartridges while maintaining supersonic velocity beyond 1,200 yards.

This combination makes it ideal for new precision shooters who can practice extensively without developing recoil sensitivity. The cartridge’s ballistic coefficient advantage becomes evident at extended ranges. Where traditional hunting cartridges begin to lose effectiveness beyond 400-500 yards, the 6.5mm Creedmoor maintains consistent terminal performance well past 800 yards, making it increasingly popular for Western hunting where long shots are common.

Competitive shooters quickly embraced the Creedmoor for Precision Rifle Series (PRS) competitions, where its accuracy, mild recoil, and excellent ballistics provide competitive advantages. This success drove ammunition manufacturers to develop extensive load offerings, from budget-friendly practice ammunition to premium match loads featuring the latest bullet technology.

The hunting community’s adoption followed as hunters recognized the cartridge’s effectiveness on deer-sized game combined with its pleasant shooting characteristics.

Today, virtually every major rifle manufacturer chambers rifles in 6.5mm Creedmoor, and ammunition availability rivals established cartridges like .308 Winchester, ensuring the Creedmoor’s continued success across multiple shooting disciplines.

.270 Winchester

The .270 Winchester stands as one of America’s most beloved hunting cartridges, earning its reputation through nearly a century of proven performance in the field. Introduced by Winchester in 1925, this cartridge was created by necking down the venerable .30-06 Springfield case to accept .277-caliber bullets, resulting in a flatter-shooting round that quickly gained favor among hunters pursuing everything from antelope to elk.

What sets the .270 Winchester apart is its exceptional balance of velocity, energy, and manageable recoil. Typical factory loads push 130-grain bullets at approximately 3,060 feet per second, while 150-grain bullets achieve around 2,850 fps. This performance delivers a remarkably flat trajectory – a 130-grain bullet sighted at 200 yards drops only about 7 inches at 300 yards, making it forgiving for hunters who must estimate range quickly in the field.

The cartridge’s moderate recoil makes it accessible to a wide range of shooters, including youth and those sensitive to heavy recoil, while still delivering sufficient energy for clean kills on deer-sized game well beyond 400 yards. Its sectional density and velocity combination provides excellent penetration on larger game like elk and moose when using premium bullets in the 150-grain range.

Jack O’Connor, the legendary outdoor writer, championed the .270 Winchester for decades, using it successfully on hunts worldwide and cementing its reputation as a versatile, reliable hunting round. His advocacy helped establish the cartridge’s reputation for accuracy and field performance that continues today.

Modern ammunition manufacturers offer extensive .270 Winchester options, from economical practice loads to premium hunting ammunition featuring advanced bullet designs. The cartridge’s widespread popularity ensures availability virtually anywhere hunting ammunition is sold, making it an excellent choice for hunters who travel or those seeking a proven, versatile hunting round.

Magnum Rifle Cartridges

.300 Winchester Magnum

The .300 Winchester Magnum has reigned as America’s most popular magnum hunting cartridge since its introduction in 1963, offering the perfect balance of power, availability, and versatility that has made it a staple from Alaskan guide rifles to African safari batteries. Winchester developed this cartridge by shortening the .375 H&H Magnum case and necking it down to .30 caliber, creating a round that fits in standard-length magnum actions while delivering significantly more power than the .30-06 Springfield.

What distinguishes the .300 Win Mag is its ability to push heavy bullets at impressive velocities across a wide range of bullet weights. Factory loads typically drive 150-grain bullets at 3,290 fps, 180-grain bullets at 2,960 fps, and 200-grain bullets at 2,800 fps. This performance translates to devastating terminal energy – a 180-grain bullet retains over 2,000 foot-pounds of energy at 400 yards, making it extremely effective on large game at extended ranges.

The cartridge’s versatility spans from long-range deer hunting with lighter bullets to dangerous game applications with heavy, premium projectiles. Its flat trajectory and retained energy make it excellent for mountain hunting where shots can range from close encounters to across-canyon distances. Many professional hunters and guides consider it the minimum for large bears, and it remains popular for elk, moose, and African plains game.

Military and law enforcement adoption has further validated the .300 Win Mag’s capabilities. Special operations snipers have used it extensively for its ability to deliver precise, powerful shots at extended ranges, while maintaining compatibility with widely available ammunition and components.

The trade-off for this performance is substantial recoil – typically 25-30 foot-pounds compared to the .30-06’s 18 foot-pounds – and increased muzzle blast. However, for hunters pursuing large or dangerous game, or those needing maximum range capability, the .300 Winchester Magnum’s proven track record and widespread support make it an excellent choice.

7mm Remington Magnum

Introduced in 1962, the 7mm Remington Magnum quickly established itself as the thinking hunter’s magnum, offering an exceptional combination of flat trajectory, manageable recoil, and deadly terminal performance that appeals to hunters who appreciate ballistic efficiency over raw power. Built on the same .375 H&H-derived case as the .300 Winchester Magnum but necked down to 7mm (.284 caliber), this cartridge maximizes the ballistic potential of the excellent 7mm bullet diameter.

The 7mm Rem Mag’s genius lies in its ability to launch high-ballistic-coefficient bullets at velocities that create remarkably flat trajectories with moderate recoil. A typical 150-grain load achieves 3,110 fps, while the popular 160-grain bullets reach 2,950 fps. These 7mm bullets, with their excellent sectional density and aerodynamic efficiency, retain velocity and energy exceptionally well downrange, often outperforming heavier bullets from larger cartridges at extended distances.

This ballistic efficiency translates to real-world hunting advantages. The 7mm Rem Mag delivers sufficient energy for elk-sized game past 500 yards while producing about 20% less felt recoil than comparable .300 magnum loads. This recoil advantage allows hunters to practice more extensively and shoot more accurately under field conditions, particularly important for the long-range shots where magnums excel.

The cartridge has earned particular favor among Western hunters pursuing elk, mule deer, and antelope across varied terrain and distances. Its ability to handle everything from 140-grain bullets for deer-sized game to 175-grain bullets for the largest North American game makes it exceptionally versatile for hunters who pursue multiple species.

Competitive long-range shooters have also embraced the 7mm Rem Mag for its inherent accuracy potential and excellent ballistic performance. The combination of manageable recoil, flat trajectory, and wind resistance makes it competitive in long-range precision shooting disciplines while remaining effective for hunting applications.

.338 Lapua Magnum

The .338 Lapua Magnum represents what many believe to be the pinnacle of long-range precision cartridge development, originally created for military snipers but increasingly adopted by civilian precision shooters and hunters who demand maximum long-range capability.

Developed in the 1980s by Finnish ammunition manufacturer Lapua in collaboration with Research Armament Industries, this cartridge was specifically designed to propel heavy .338-caliber bullets with extreme accuracy at distances exceeding 1,500 yards.

Built on a case derived from the .416 Rigby but optimized for modern powder and precision manufacturing, the .338 Lapua pushes massive bullets at impressive velocities. Factory loads typically drive 250-grain bullets at 2,900 fps and 300-grain bullets at 2,650 fps, generating muzzle energies exceeding 4,800 foot-pounds. More importantly, these heavy, high-ballistic-coefficient bullets retain their energy exceptionally well, maintaining over 2,000 foot-pounds at 800 yards.

What sets the .338 Lapua apart is its engineered precision. Every aspect of the cartridge – from the case design and primer pocket specifications to the bullet manufacturing tolerances – was optimized for extreme accuracy. This attention to detail allows properly configured rifles to achieve sub-minute-of-angle accuracy at distances where other cartridges struggle to remain supersonic.

Military adoption validated the cartridge’s capabilities, with snipers using it for confirmed kills beyond 2,400 yards. This battlefield success drove civilian interest among precision rifle competitors and extreme long-range hunters. The cartridge dominates King of 2-Mile competitions and similar extreme-distance events where accuracy at unprecedented ranges is paramount.

The .338 Lapua’s hunting applications focus on situations requiring maximum range and stopping power – dangerous game at distance, elk hunting in open country, or situations where a single, precisely placed shot is critical. However, the cartridge demands respect: recoil approaches 40 foot-pounds, ammunition costs $3-5 per round, and rifles capable of utilizing its potential typically weigh 12-15 pounds with optics.

For shooters seeking the ultimate in long-range precision and terminal performance, the .338 Lapua Magnum represents the current state of the art, offering capabilities that were considered impossible just a generation ago.

Lever-Action Rounds

.30-30 WCF

The first American-made centerfire cartridge loaded with smokeless powder, the .30-30 (“thuddy-thuddy”) was first introduced with the Winchester Model 1894 in the final decade of the 19th century.

Since then, it has remained the most common chambering for lever-action rifles. Using bullets ranging from 120- to 170-grain, it is often said that “more deer are shot with a .30-30 than any other rifle” in North America.

.45-70 Government

Probably the oldest centerfire rifle round in serious production these days, this cartridge was adopted by the U.S. Army in 1870 for use in single-shot Springfield trapdoor breechloaders and originally utilized a 405-grain .45-caliber bullet over a black powder load, earning it the original designation as the .45-70-405.

Over the years, the cartridge has been upgraded with a smaller, more efficient bullet, and smokeless powder.

Today is it most seen in “cowboy guns” by Chiappa, Marlin, and Henry, still clocking in with hunters who appreciate the heavy soft point.

.35 Remington

A throwback to the days when hunters packed a lever-action carbine for hunting anything from deer to elk and bear, the big honking .35 Remington offered a fat bullet – up to 200-grains – in a package with a low enough recoil to function in a small-framed carbine.

This combo has kept the cartridge, as well as rifles that use it, in production since 1908.

.44 Magnum in Rifle Applications

While the .44 Magnum gained its legendary reputation through Clint Eastwood’s “Dirty Harry” films and powerful revolvers, this versatile cartridge truly shines when fired from rifle-length barrels. The additional barrel length transforms the already potent handgun round into a formidable short to medium-range hunting cartridge, making it particularly popular in lever-action rifles and semi-automatic carbines.

The performance difference between handgun and rifle applications is dramatic. Where a 6-inch revolver might push a 240-grain bullet at 1,200 fps, an 18-inch rifle barrel can achieve velocities approaching 1,800 fps with the same load. This 600 fps increase translates to significantly more energy – often exceeding 1,700 foot-pounds at the muzzle compared to less than 800 foot-pounds from a handgun.

This enhanced performance makes the .44 Magnum rifle an excellent choice for deer hunting in areas with restricted rifle zones or for hunters who prefer the quick-handling characteristics of lever-action carbines. The large, heavy bullets (typically 200-300 grains) create substantial wound channels and penetrate deeply, providing reliable terminal performance on medium game within 150-200 yards.

The cartridge’s popularity in rifle applications stems largely from its use in iconic firearms like the Marlin 1894 and Ruger Deerfield carbines. These lightweight, fast-handling rifles offer the perfect platform for the .44 Magnum’s capabilities, providing enough power for serious hunting while maintaining the portability needed for thick cover or stand hunting where quick target acquisition is crucial.

Modern rifle applications have expanded beyond traditional hunting to include home defense and tactical uses. Semi-automatic carbines chambered in .44 Magnum offer substantial stopping power with manageable recoil in a compact package, though ammunition costs and limited magazine capacity compared to intermediate rifle cartridges remain considerations.

The .44 Magnum’s straight-walled case design has gained renewed relevance as many states have legalized straight-walled cartridges for deer hunting in previously shotgun-only zones. This regulatory change has sparked increased interest in .44 Magnum rifles as they offer significantly better ballistic performance than traditional slug guns while remaining compliant with local hunting regulations.

For hunters and shooters seeking a powerful, reliable cartridge that performs well in short, handy rifles while remaining effective on medium game, the .44 Magnum represents an excellent balance of power, practicality, and traditional American shooting heritage.

Shotgun Ammunition

While plenty of .410 and .20-gauge shotguns are sold every year, and the 16-gauge is making something of a comeback, by far the most popular shotgun is the 12-gauge, making it a common denominator when it comes to scatterguns.

Selecting the appropriate shotgun gauge depends on the intended use, such as hunting, sport shooting, or home defense.

With that being said, 1.75-inch mini shells, 3-inch magnum, and 3.5-inch super magnum length shells are in widespread circulation, but the standard is 2.75-inch shells, with almost all modern 12 gauges set up with a chamber to accommodate that size.

The amazing capability of the 12 is attributed to the variety of loads on the market, including less-lethal, low brass birdshot, high brass field shot, non-traditional loads such as bismuth and steel rather than lead, buckshot, slugs and exotic specialty rounds.

Handgun Cartridges

The 9x19mm Luger, .40 Smith & Wesson, and .45 AUTO are among the most popular pistol cartridges. Many of these calibers are commonly selected for personal defense due to their balance of power and manageable recoil.

9mm Luger

Although long snubbed by American gun owners, likening it to a spitball compared to homegrown handgun calibers, the 9x19mm cartridge was designed in 1902 by Austrian gunsmith Georg Luger for his namesake pistol.

Immediately popular in military service – the German army adopted it just five years after it was introduced — the 9mm has been embraced in the U.S. relatively recently (in the 1960s and 70s) with advances in bullet technology that wiped away performance concerns.

It has since become the equivalent of 87-octane (if the semi-auto handgun market ran on gasoline).

Today, most law enforcement agencies in the U.S., including the FBI, depend on the cartridge, and more than 5 million 9mm pistols were made in the country in 2018 alone. Typical loads run between 115- and 147-grains.

9mm loads typically deliver between 300 and 400 ft lbs of muzzle energy, providing reliable stopping power and penetration.

We cover the best 9mm handguns if you’re in the market for a firearm that uses this classic round.

.40 S&W

Introduced in 1990, the .40 Smith & Wesson was designed as a pistol cartridge that combined the power of the 9mm with a higher magazine capacity than the .45ACP.

It remained the preferred choice for law enforcement and personal protection for about 25 years, until the FBI reverted to the 9mm in 2015.

Make no mistake, though, with loads ranging from 135- to 180-grains, the .40S&W is still in demand and ready to deliver.

For those interested in these cartridges, we compare the .40S&W to the 9MM here.

.45ACP

Designed in 1904 by John Browning in response to the U.S. Army’s request for a more effective handgun round, the .45 ACP is closely associated with Mr. Browning’s M1911 pistol, which remained a standard in American military service for 75 years.

The chunky cartridge, with the typical bullet weight clocking in at 230-grains, endures today and recently surpassed the .40S&W to become the no. 2 bestselling pistol round in the country, only surpassed by the 9mm.

We’ve got a list of our favorite .45 ACP pistols if you’re interested.

.380 ACP

The .380 ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol), also known as 9mm Short or 9x17mm, represents the most popular pocket pistol cartridge in America, striking a careful balance between adequate stopping power and ultra-compact firearm design.

Developed by John Moses Browning in 1908 for his Colt Model 1908 Pocket Hammerless pistol, this diminutive round has experienced a remarkable resurgence in the concealed carry era.

What makes the .380 ACP appealing is its ability to function reliably in extremely small pistols that would be impractical with larger cartridges.

Modern .380 pistols can weigh as little as 8-12 ounces and measure less than an inch thick, making them genuinely pocketable for deep concealment situations where larger firearms would be impossible to carry discretely.

Performance-wise, the .380 ACP typically pushes 90-95 grain bullets at 900-1,000 fps from short barrels, generating 200-250 foot-pounds of muzzle energy – significantly less than larger defensive cartridges but adequate for close-range personal protection when quality ammunition is used.

Modern defensive loads featuring hollow-point bullets designed specifically for the .380’s modest velocity have dramatically improved the cartridge’s terminal effectiveness compared to older full metal jacket loads.

The cartridge’s popularity exploded with the concealed carry movement and introduction of modern micro-pistols like the Ruger LCP, Glock 42, and SIG P238.

These firearms made it possible for people to carry a centerfire pistol in situations where previously only pepper spray or similar less-lethal options were practical – pocket carry, ankle holsters, or ultra-discrete body carry.

Limitations include modest stopping power compared to service cartridges, limited effective range (typically under 25 yards), and the challenge of finding ammunition that expands reliably at the .380’s lower velocities.

However, for individuals who prioritize concealability above all else, or those with physical limitations that make larger firearms difficult to handle, the .380 ACP provides a viable self-defense option in an extremely compact package.

The key to .380 ACP effectiveness lies in ammunition selection and shot placement. Modern defensive loads from manufacturers like Federal HST, Hornady Critical Defense, and Speer Gold Dot are specifically engineered to perform at .380 velocities, making this historic cartridge far more effective today than when it was first introduced over a century ago.

10mm Auto

The 10mm Auto stands as one of the most powerful semi-automatic pistol cartridges in widespread production, offering rifle-like performance in a handgun platform while maintaining the rapid-fire capability that makes semi-automatic pistols attractive for both defensive and hunting applications.

Developed in 1983 by Jeff Cooper and Dornaus & Dixon Enterprises, the 10mm was designed to bridge the gap between the 9mm’s capacity and the .45 ACP’s stopping power.

The cartridge’s impressive ballistics speak to its potency: factory loads commonly push 180-grain bullets at 1,250 fps and 200-grain bullets at 1,200 fps, generating over 1,300 foot-pounds of muzzle energy – performance that rivals many rifle cartridges.

This power level makes the 10mm effective on medium game like deer and wild boar, leading to its adoption by hunters who appreciate the quick follow-up shots possible with a semi-automatic platform.

Law enforcement adoption, particularly by the FBI in the late 1980s, validated the 10mm’s effectiveness but also revealed its limitations.

While the cartridge delivered devastating terminal performance, the substantial recoil and muzzle blast proved challenging for many agents to manage effectively. This led to the development of reduced-power “FBI loads” and eventually the creation of the .40 S&W as a more manageable alternative.

The 10mm experienced a renaissance in recent years as civilian shooters rediscovered its capabilities. Modern pistols like the Glock 20, Springfield XD-M, and various 1911 variants handle the cartridge’s power more effectively than earlier designs, while improved manufacturing has made quality ammunition more widely available.

The cartridge has found new life among outdoorsmen in bear country, where its combination of power and rapid-fire capability provides confidence against dangerous wildlife.

Versatility represents another 10mm advantage. Light, fast loads (135-155 grains) provide excellent performance for self-defense with manageable recoil, while heavy loads (200-220 grains) deliver the power needed for hunting applications.

This range allows shooters to tailor their ammunition choice to specific applications while using the same firearm.

The trade-offs include substantial recoil that requires practice to master, expensive ammunition compared to more common cartridges, and the need for robust firearms capable of handling the cartridge’s high operating pressures.

However, for shooters seeking maximum power in a semi-automatic platform – whether for wilderness protection, hunting, or those who simply appreciate the 10mm’s impressive capabilities – this cartridge delivers performance that few handgun rounds can match.

Revolver Rounds

Revolvers are popular for their reliability and simplicity, and they are commonly chambered in a variety of calibers.

Revolvers are versatile firearms that can shoot a wide range of bullet sizes and types, making them suitable for different shooting needs. Some of the most popular revolver rounds include the .38 Special, .357 Magnum, and .44 Special.

.38 Special

Hailing back to 1899, the .38 Smith & Wesson Special hit the market in S&W’s new Military & Police revolver just after the Spanish-American War and has been going strong ever since.

Since the 1940s, it has been the most popular wheel gun round, displacing older “cowboy” cartridges. Amazingly cheap for target use when buying unjacketed lead bullets, the .38SPL continues to clock in as a reliable self-defense round with good JHPs, especially in +P loads. Typical loads range from 110- to 158-grain bullets.

.357 Magnum

Introduced in 1934 and popularized by iconic revolvers like the Colt Python in the 1950s, the .357 Magnum is slightly longer than the older .38 Special, meaning handguns chambered for .357 can also fire the .38 Special.

The extended case of the .357 allows for greater power, even though it uses bullets similar in size to the .38.

We’ve got a guide to everything .357.

.44 Special (and Magnum)

Revolvers chambered for .44-caliber black powder loads such as .44 S&W (Russian) and .44-40 Winchester were extremely popular in the 19th Century.

By 1907, Smith & Wesson had updated this concept, introducing the smokeless powder .44 Special. With its substantial 200+ grain bullet, it became a top choice for those seeking a powerful round for serious business.

Fast forward to 1955, and the .44 got the Magnum treatment in much the same way as the .38 Special led to the .357 Magnum.

Pocket and Backup Gun Cartridges

.22 LR

Hitting the market in 1884, the humble .22 Long Rifle rimfire round is a pipsqueak when compared to a .30-06, 5.56mm NATO, or 9mm, but it is widespread in use as a target and plinking round, for small game hunting, and, in a pinch, self-defense.

Used in rifles, pistols, and revolvers, the .22LR is about the most affordable cartridge that can be bought when it comes to the price-per-round cost.

That is something that will keep this useful little round in circulation for decades to come.

.17 HMR

The .17 Hornady Magnum Rimfire revolutionized small-game hunting when introduced in 2002, offering unprecedented accuracy and flat trajectory in a rimfire cartridge. Based on the .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire case necked down to .17 caliber, the .17 HMR pushes lightweight 15.5-20 grain bullets at velocities exceeding 2,500 fps.

This performance creates a laser-flat trajectory out to 150 yards, making it devastating on prairie dogs, ground squirrels, and similar small varmints. The cartridge’s explosive terminal effects on small game are dramatic, though this limits its use on larger targets like rabbits where meat preservation matters.

]Modern bolt-action and semi-automatic rifles chambered in .17 HMR deliver exceptional accuracy, often achieving sub-minute groups that rival centerfire varmint cartridges at shorter ranges.

.25 ACP

The .25 ACP represents the smallest centerfire cartridge in common production, designed by John Browning in 1905 for ultra-compact pocket pistols where concealability takes absolute priority over stopping power. Pushing tiny 35-50 grain bullets at modest 750-900 fps velocities, the .25 ACP generates minimal recoil and muzzle blast while functioning in pistols small enough to fit in a shirt pocket.

Historical examples include the Baby Browning and Beretta 21A, firearms that prioritize discretion over effectiveness. While the cartridge offers minimal stopping power compared to larger options, its ability to function in truly tiny firearms made it popular for backup guns and deep concealment applications.

Modern shooters generally favor the more effective .380 ACP in similarly-sized firearms, relegating the .25 ACP to specialized collectors and those requiring maximum concealability regardless of performance limitations.

Closing thoughts

No matter the assortment of ammo you go with, be sure to keep it dry while saving on a per-round basis when you can by “buying it cheap and stacking it deep.”

And of course, if you do, consider a dedicated ammo safe to ensure your ammo can be stored safely and securely, especially over the long haul.

Additional Resources

- Military.Wikia.Org, Jean Samuel Pauly

- Wikipedia, Pinfire Cartridge

- Ammo.com, Lead Round Nose Ammo

Updated

May 27, 2025 — Updated multiple sections and added a number of cartridges missing from the previous iteration of the article.

Sign up for our newsletter

Get discounts from top brands and our latest reviews!